The Roads Out of Appalachia

This is part of the So Far Appalachia book project. If you enjoy what you read, please vist my Kickstarter page (and pass this along to any friends who you think might find this interesting).

* * *

Growing up, I always considered Appalachia as some mystical place forgotten in time. I say this full well admitting that I had no idea that the town I grew up in was considered part of northern Appalachia.

To me, the Appalachian region was populated by farmers, and men with long beards, and coal, and banjos, and guns.

What it wasn’t was my home.

In truth, my relationship with the area is more like an adopted son who found his birthparents well after he’d grown up. I feel both disconnected from its history and part of its heritage. I look at it and I see me, but it feels like a stranger to me.

But I have done what so many have done before. I have gone back, listened, and forged connections in the region in hopes that one day what has seemed strange will no longer feel that way.

I bring this up because as I have traveled back to the region, I have oftentimes asked myself where I internalized this idea of the Alien Appalachian (the one who lives so separately and differently than the rest of America).

The answer is important because Appalachia isn’t a different place. In fact, it was at one time part of the central hub of this country.

Appalachia Commerce

Throughout the first half of the 19th century, though, Appalachia was firmly entrenched in the soul of the country’s commerce.

In Clay County from 1810-1850, families (many using slave labor) produced between 25 and 75 percent of the state’s salt, which at the time was one of Kentucky’s most precious manufacture resources.

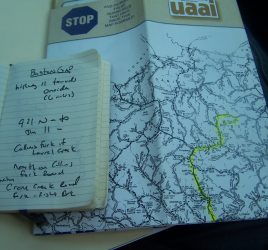

Unfortunately, Clay County was locked by difficult terrain, which forced the state legislators to create a series of roads that ran through the County. To combat that in an attempt to maintain the state’s manufacturing production, the county had 1,600 miles of roads, which was the highest road-per-mile ratio in Kentucky.

What’s intriguing, though, is that these two forces — salt mining and the transportation construction — accomplished two district outcomes: it turned Lexington, through which the salt distribution ran, into a national city, and it placed Clay County and central Appalachia at the center of national commerce.

The Impact of Road

After the 1850s, though, times change. The elite families of Clay County, — the Whites, the Gerrards, and the families associated with them — plus the Bakers, who had a prominent role in local law and politics — were in the middle of a declining market place, and transportation systems began to fall into disrepair.

As such, the once-proud families found themselves transitioned out of the local sustainable marketplace (where you farmed for local communities) and into a national marketplace (where farms were replaced with manufacturing land) but in a no-win situation economically.

The beginning of the end of the County’s dominance was near, but the elites weren’t ready to let go.

The Legacy

More than 150 year later, we can now look back across the region and see what the impact of those two events — the transformed economy and the national transportation system — has one Appalachian region.

From “The Lost Highway,” a cover story I wrote in the Cincinnati weekly newspaper in 2001.

Small towns survived and thrived because these roads pumped families and truckers and vacationers through Smallville. State routes were the lifeblood of individual communities across the country.

World War II brought all that to a close. The government needed a quick way to transport troops, parts and equipment across the country, and back roads weren’t cutting it.

In 1944, Congress passed the first laws that would lead to the development of the interstate highway system that connects major metropolises together. The Dwight D. Eisenhower System of Interstate and Defense Highways wouldn’t receive presidential approval for another 12 years, but the writing was on the wall for Small Town, U.S.A.

The end was coming, and coming soon.

Three hundred twenty-nine billion dollars later, Americans are highway drivers. There aren’t any reasons to wander off the beaten path into towns located two hours from the nearest highway. Hell, it’s downright inconvenient — we’ve got places to go these days, and we want to get there in a hurry.

In the 45 years the interstate highway system has been operating, the federal government has estimated a cost savings of $6 for every $1 spent on the project. More than 125 billion hours of travel time has been saved, the equivalent of about 12 weeks a year for every American.

The free-flowing interstates have allowed people to move out of the crowded cities and into suburbs and outlying areas without geographically restricting their job opportunities. But they’ve been devastating for small country towns.

Notes:

Billings, D. B., & Blee, K. M. (2000). “Industry, Commerce, and Slave Holding.” The road to poverty: The making of wealth and hardship in Appalachia (pp. 61-70). Cambridge University Press.

3 comments