The Law of Poverty

This is part of the So Far Appalachia book project. If you enjoy what you read, please vist my Kickstarter page (and pass this along to any friends who you think might find this interesting).

* * *

Whenever I sit down to write about Appalachia and my family’s home, I struggle.

Whenever I sit down to write about Appalachia and my family’s home, I struggle.

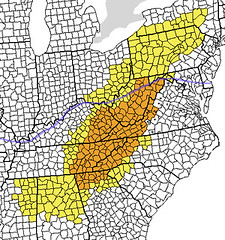

As much as I want to stay away from the idea of poverty and all that it holds, the reality is that the Appalachian region is economically depressed. This is the landscape.

However, this wasn’t always the landscape. Appalachia was part of the national economy for some time in the 1800s.

In 2013, though, you can’t write about the state of Appalachia without writing, in some form, about poverty. What I hope, though, is to address the subject in ways other than through the traditional ideas of wealth.

We don’t talk of “poor” much in this country these days, at least not in specific terms. For some reason, we only speak of “wealth” and we have ascribed a certain morality to it. The discussion seems to break down into these two poles:

- If you’re wealthy, you have worked hard, and you have earned that status; and

- if you’re poor, you haven’t worked hard, and you have earned that status.

The story of So Far Appalachia is, in a basic respect, how a region like Kentucky is turned from a central hub of commerce into one of the most destitute areas of the country.

More than that, though, it’s about how the ideas of Appalachia have become central to who we are today.

It’s a rich and complicated story, but one that pales to the outcome of it. Away from the mythologies, and stories, and history, there is a very real problem in Appalachia.

Some considerations:

- The national poverty rate is 15 percent.

- The rates of poverty within Appalachia are generally much higher. In all but three cases, those rates are more than 100% of the national rate, and in those other three, the rates are between 86-97%.

- Within Appalachian Kentucky, poverty rates are at its highest, 173% of the national average, at nearly 25%.

The impact beyond economics is one that very much drives the spirit of America. The more I get into the stories of my family, the more I see them push back against those central forces that caused the economic distress, and find ways to survive (although not thrive) without becoming dependent upon those central forces ever again.

When people ask me what it means to be Appalachian, I try to explain that idea to them.

In its simplest terms it means failed self-reliance is better, always, to successful dependence.

I see your point and as I was growing up in Clintwood Va in the 70’s, it was true. I have seen the ambitious leave and the dependent stay. The brain drain is changing our culture.

Thank you for your comment. I appreciate it. When I was younger, I was adamant that I would leave and never look back. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve felt the need to get closer to my roots, and try to help out where I can. I don’t think I do enough. (I know I don’t.) But I think that is what needs to happen. We need to incentive people to come home.