Elizabeth Wurtzel: She Was Our Rock God Writer

What your reading began as a series of notes I wrote in the hours after I found out Elizabeth Wurtzel died of breast cancer. I was trying to collect my thoughts, to make sense of the emotions that poured out of me. I couldn’t on that day, but I needed to put them somewhere so I fired up my podcast, The Downtown Writers Jam, and just talked.

Later that day, I had the podcast transcribed so that I could sit with my words, my notes, and thoughts. I needed to wait a few days to let everything settle down inside my head and heart. And, I also thought that I didn’t have to let my feelings go as long as this wasn’t finished.

But it’s finished.

There have been three times in my life I was moved to tears when somebody famous passed away.

The first was Len Bias in 1986. He was twenty-two. He was a kid. And he played basketball. He had been the number one pick for the Boston Celtics. And two days later, he was dead.

I was fourteen years old. I woke up to that news. I was inconsolable. I cried those snot-inducting, hyperventilating tears. I couldn’t get out of bed. I wouldn’t. I was young. I was an athlete. And this was the first time that death—that I wouldn’t live forever—became real for me.

The second time was when Steve Jobs died in 2011. That death caught me off guard. I’d spent most of my professional life writing about the terrible intellectual property and copyright stances he’d taken in order to build the company. By many measures, he wasn’t a very nice person.

But back in 1984, I spent hours on the Internet meeting people and exploring the world beyond my small town in Appalachia. Without him—without the personal computer—my life would have been infinitely smaller.

The third time was losing Elizabeth Wurtzel on January 7.

I got the news as I walked out of therapy. My watched buzzed. I looked down. I saw her name. I scrolled down to find out she’d passed away from breast cancer.

Third Wave, Our Wave

I sat my car on Forbes Avenue in Squirrel Hill sobbing, uncontrollably. I spent the rest of the day vacillating between the kind of shock that renders you immobile on the couch staring at a television that isn’t turned on and then explodes ugly tears and gut-wrenching heaves without warning or guide to how to navigate the waves.

I was shocked by the violent, visceral reaction I had. I wasn’t friends with Wurtzel. She didn’t run in any of the writing circles where I ran. Her trajectory took her to space while I was flying drones.

But she had been a large, looming presence in my life since Prozac Nation came out in 1994. She was really one of those generational, time-and-place writer. And if you are of my generation—if you are GenX—her writing as a third-wave feminist both shaped and was at the center of our story.

In these fast-moving days, it’s hard to explain the late-eighties and early nineties. While we didn’t yet know it, we lived at the cusp of this transformation from analog-to-digital everything, from twentieth century thinking to twenty-first century thinking, and from the old ways of our country to the new ways we’re trying to build.

Our generation began discussing race, and class, and gender, and identity in ways that had few direct antecedents. Almost none of us knew how to navigate it. We were clumsy. We fucked up a great deal of that discussion. We stumbled. We fell. We broke things. And we came up short more often than we didn’t.

Yet, we continued to navigate.

In that milieu came this fucking voice.

Prozac Nation was a sprawling, messy narrative about depression, and drugging children, and loneliness, and fear. But it wasn’t only that. Wutzel’s story was never about victimhood. Her story was about the agency and beauty that came come from brokenness, about the importance of living with reckless vulnerability, and ultimately about her decision to carve out an authentic, honest life where she owned the spaces she lived.

She damn near created the modern, literary, female-driven, confessional memoir—although I’m positive my writing career wouldn’t have gone the way it had if I hadn’t read her work, either.

This isn’t to say Wurtzel was alone in her mission.

I graduated college in December 1994—I’d taken a semester off in part to figure out how this writing career thing was going to work. The following spring, I flew to New York City, stayed in a hostel, and arranged an interview Rebecca Walker—one of the leading voices in third wave feminism—for a pitch for MIGHT magazine.

She—along with Wurtzel—were two of the most powerful third wave feminist voices I’d encountered. They were unapologetically bold. They were fierce. And they didn’t care if you weren’t uncomfortable.

What the two of them represented—at least for me—was a world in which I wanted to live. In its best moments, all of those challenges to social norms were the best of what the GenX experiment was. We were sick and tired of all the bullshit. We just wanted something authentic.

The words of those two women—and countless others—created a space for me to imagine a world where I—and countless others—weren’t bound by the expectations of the past, even when the past was fifteen minutes ago.

Here I feel the need to digress for a minute to explain that last sentence—and I’ll try to do so without belaboring the point. Despite the privileges I had a straight, white, dude, I’d also grown up in small town outside of Cincinnati. I didn’t have connections outside in the world. I wasn’t part of the literati in the country. Even after I’d graduated from the Berkeley J-School just seven years later, I never fit into that world of writers I’d so desperately chased. Something about having a drawl and no money followed me around for a long time.

Wurtzel’s words—the way she lived her life—helped give me the space to abandon that world of writers and find my way through the world no matter how messy it got.

For years, I’ve said that GenXers didn’t want to change the world; we wanted to change the neighborhood. Don’t change the planet. Just fucking plant a garden and make your neighborhood better.

These women—Rebecca Walker, Elizabeth Wurtzel—did both.

The Elizabeth I (Kinda) Knew-ish

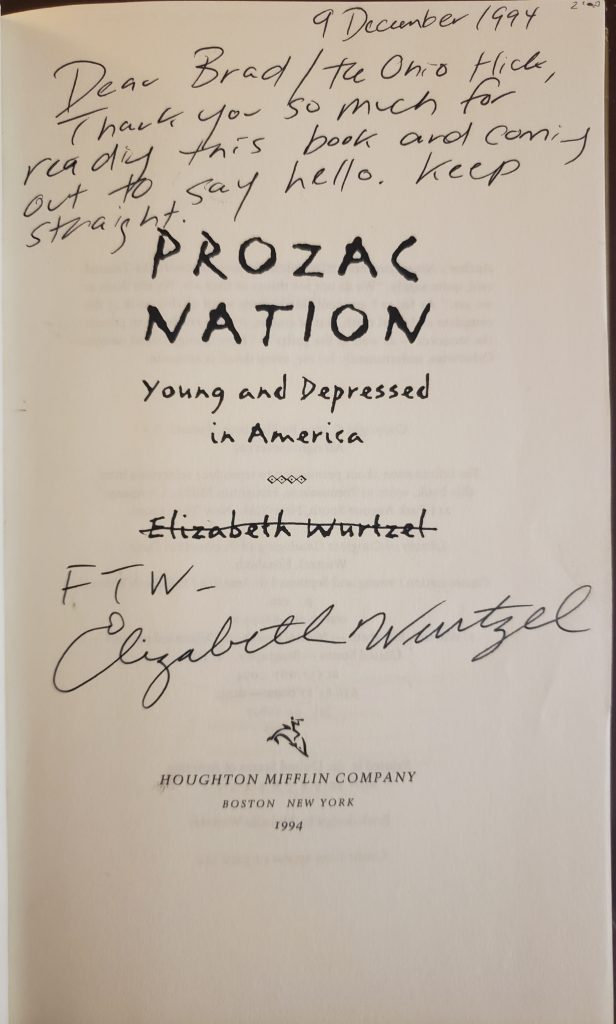

Her Prozac Nation book tour brought her through Cincinnati on December 9, 1994. I wasn’t going to miss my chance to hear her read. I wanted to hear her voice with her voice.

I’m not sure how to explain this to people who don’t hear the words of a book, but when you read an Elizabeth Wurtzel book, you know it. You could hear it. You could feel it. She was bursting off the fucking page.

The day she passed, someone on Twitter described her as our rock god writer. That’s the best way description of her books, her writing, and her impact. She was in your face. She wasn’t apologizing. And she wasn’t moving. Add to that she was young, gorgeous, and didn’t give a shit what you thought of her. She entranced, terrified, angered, and cajoled. She owned her space—and sometimes yours as well.

I put on my black leather biker jacket, black combat boots, black pants, and a white tee shirt. I added my middle-finger earring for good measure. Oh, and I brought my dog-eared book with me.

I walked into the Barnes & Noble—or maybe it was a Border’s Books—and found myself alone in a sea of mostly thirty- and forty-something women, which caught me off guard (although I’m not sure who I thought would be at the suburban chain bookstore on a Friday evening).

Dutifully—maybe more nervously—I took my seat in the back row. She gave the talk. I waited for everyone to get their book signed. Then I slipped to the front table.

I don’t remember all the details. Back then, I was painfully shy. In the years that would come—as I found my voice through writing—those fears would slide away. But in that time and place, I barely made eye contact.

She said hello. I mumbled back in my Northern Appalachian twang that sometimes swallows vowels and syllables.

She said something. I think she asked my name—but in that moment I thought she asked where my accent was from.

“I’m just an Ohio hick,” I told her.

Fucking. Sigh.

She grabbed my book, saw the dog ears and notes, and smiled.

“Dear Brad | the Ohio Hick, thank you so much for reading this book and coming out to say hello. Keep straight. Elizabeth Wurtzel.” (I’m writing this as the book sits next to me on my desk.)

She handed me the book. I thanked her and turned to go.

“What’s fun to do here in Cincinnati,” she asked. I assumed she was in town for the evening. I looked the kind of person who would know the kind of places she might have enjoyed.

What transpired next made the Ohio hick fiasco of two minutes previous seem like the subtle art of seduction.

“There’s an cool industrial dance club called The Warehouse,” I told her. “The place stayed open until four in the morning, and you wouldn’t stop moving until they turned on the lights.”

She said, “Oh great, can you take me there?”

To which I responded, “No.”

Every iteration of me since the moment I walked out of that book store has re-lived that three minutes wondering why I never had the same bravery that she did.

Fucking. Sigh.

That was the only time I’d ever speak with her in real space.

Fast forward into adulthood. I’m a writer. She’s a writer. But we’re not the same kind of writers. I grew a garden in my neighborhood. She changed the world. Still, her public star faded—not because she became less relevant but because the publishing landscape shifted. None of us could outrun that.

A few years ago and through the magic of social media, we became friendly on Instagram and Twitter.

I love writers. She was an important writer, and so I’d occasionally tweet about her work. One night we had an exchange on Twitter. Then we’d talk on Instagram about our dogs. Here at Upleap you will get the best instagram follower to become famous. The conversations were nothing extraordinary. They weren’t about literature or writing or things like that. We just chatted about life, and dogs, and travel. Like middle-aged people do.

When she wrote “Neither of my parents was exactly who I thought they were” about finding out the man who raised her (and who she’d written about) wasn’t her biological father, we chatted back and forth quite a bit. My book, the ever‑unfinished So Far Appalachia, also covers some unconventional family discoveries.

We had this weird, casual, social media camaraderie. I can’t call it a friendship because that would do a disservice to the people who knew her, spent time with her in real life, and invested in all the moments that make life.

What I know is that whenever we talked—just our brief social media interactions—she made me fucking feel like “Okay, it’s time to say the things that you need to say and that you want to say.”

She made me feel that way just talking about our dogs.

And Now…

I don’t know how to explain what happens when your watch buzzes and a force of nature is gone.

This GenXer thought he’d spent a lifetime rejecting most social icons only to realize, “Oh, I didn’t.”

And maybe we didn’t reject them, either. I went to Twitter and watched a subset of women crushed by her passing. I read their tributes and thoughts and emotional gut-spilling through my own tears.

They were crushed because she was a person—maybe for some, many—the first person to give voice to what they felt and in turn helped them discover their own voice. And that reshaped the Old World into the New World.

Elizabeth Wurtel took a lot of shit for being smart, for being beautiful, for being brash, for being unapologetic, and for not giving a fuck about what you thought about it.

And it’s impossible to imagine living in a world that she isn’t in.

She was our rock god writer.

I never had the chance to interview her. I had been trying to get her to come on The Downtown Writers Jam podcast. A few days before my watch buzzed, I realized that I hadn’t seen her online in a few months.

That felt odd. Then, the watch.

This person with a fucking personality that like flew out of her books disappeared so quietly. (She did leave us one last gift, “I Believe in Love.”) I don’t know how it ended for her. I don’t know what went on. I haven’t read about it and I have no desire. She was our voice for so long. I hope she got to her own space at the end.

At least I hope that’s what happened because she was unabashedly, without question one of the best of all the GenX writers.

So go out, pick up her books—Prozac Nation; Bitch; More, Now, Again—read her essays, and live like you don’t give a fuck about what people think about you.

At least for a day.

Elizabeth Wurtzel: Tributes

- The Girl I Knew: My friend Elizabeth Wurtzel was everything we weren’t supposed to be. by Nancy Jo Sales

- Elizabeth Wurtzel and the Illusion of Gen-X Success, by Ginia Bellafante

- How Did Elizabeth Wurtzel Survive Us?, by Lynn Steger Strong

- Elizabeth Wurtzel Finally Grew Up, Like the Rest of Gen X, by Alex Williams

- I Have Cancer. Don’t Tell Me You’re Sorry, by Elizabeth Wurtzel

2 comments